Discussion

Mesotheliomas are known to be rare mesenchymal neoplasms arising from the serosal linings of the pleura and the peritoneum and may rarely even originate in the pericardium, tunica vaginalis or the

ovarian epithelium (1,2). While simultaneous peritoneal and pleural involvement is found in 30%–45% of cases of mesotheliomas, solitary peritoneal involvement accounts for only 10%–20%

(3). The malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) was first described in 1908 by Miller and Wynn and register an overall incidence of one to two cases per million (3). Currently, about 50% of the

patients have occupationally been exposed to asbestos (1). The relationship between asbestos exposure and the malignant mesothelioma is an established fact, especially crocidolite fibers which appear

to be much more carcinogenic than amosite and more easily degraded. This suggests that a chronic irritation of mesothelial cells is important in the tumoral development. Strikingly, peritoneal

mesotheliomas are found more frequently in employees in the shipping industry. The precise pathogenesis of the peritoneal mesothelioma is not known. Animal studies show there is an evident migration

of asbestos fibers through the intestinal mucosa. However, transportation of asbestos particles from the lungs to the peritoneal cavity by the lymph system is also described (2). More recently,

radiation has been recognized as an etiologic factor. Most post-radiation mesotheliomas occur within prior radiation treatment fields, and the mean time between radiation exposure and mesothelioma

formation is approximately 19.5 years (4). A paraneoplastic syndrome has rarely been reported in the case of this tumor (1). Before the third decade, no risk factor is usually found (5). Some

investigators argue that MPM may be related to a more prolonged and heavy asbestos exposure than those with primary pleural tumors. The disease is more commonly found in men, possibly because of the

higher male occupational exposure to asbestos, in the fifth and sixth decades, although it can be seen inthose of any age group (1). The main clinical symptoms are a diffuse abdominal pain, cramps,

increasing girth and weight loss (3). Histopathologically, MPM is divided into three specific types: epithelial, fibrous (sarcomatoid) and mixed or biphasic (5). The epithelial type, the most common,

is subdivided into four subtypes: papillary, tubulopapillary, cord-like and sheet-like or solid (5). Most non-invasive diagnostic efforts are not helpful. Chest radiographs reveal evidence of

asbestosis in fewer than 45% of cases. CT scanning of the lower thorax may be helpful in revealing pleural plaques, which are compatible with asbestosis. The abdominal radiographic appearance is

non-specific and includes fixation and serosal changes of bowel loops, areas of dilatation and a narrowing of the small bowel with or without partial obstruction and fixed segments of small bowel

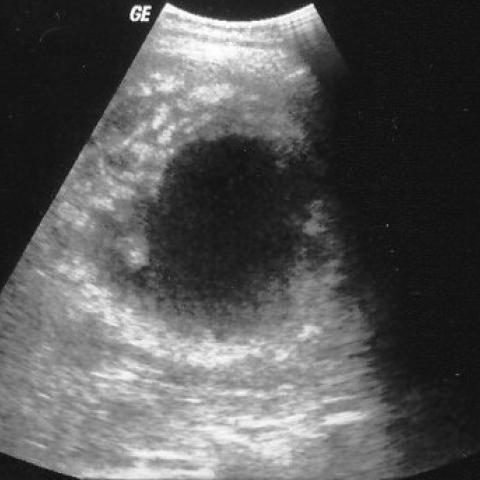

loops. Such a picture is similar to implants seen from many neoplasms. Ultrasound studies have shown that there is an associated thickened peritoneum, peritoneal nodules, omental mass and ascites

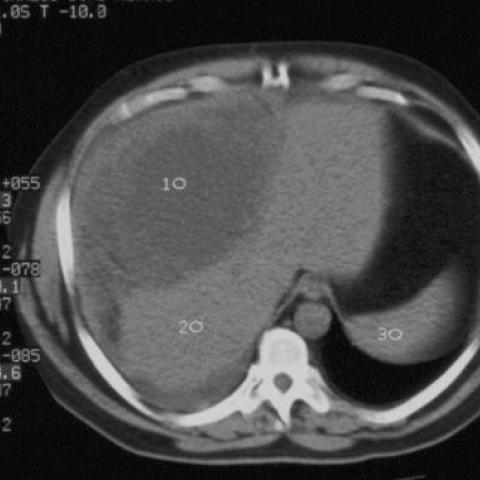

(4). In the literature, there are reports of metastatic liver and bone involvement. At abdominal CT, MPM typically appears as a solid, enhancing soft-tissue mass within the mesentery, omentum or the

peritoneum. It may also appear as an infiltrating mass or multiple nodules, varying from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter in any location within the omentum, mesentery and

peritoneal folds. It has a tendency to spread along serosal surfaces and for a direct invasion of both solid and hollow intra-abdominal organs, most commonly the colon and the liver (1).

Contrast-enhanced, fat-saturated MR imaging is a useful method for identifying the peritoneal involvement (4), in a malignant mesothelioma. In fact, increased peritoneal permeability resulting from

peritoneal carcinomatosis causes peritoneal enhancement. Also, imaging in the coronal plane is particularly useful for showing subdiaphragmatic and paracolic peritoneal implants and for delineating

the extension of the peritoneal tumor. Low et al has been indicated that the malignant peritoneal tumors are generally thicker and more lobular or masslike than benign peritoneal tumors (4). Early

stage MPM may present only as peritoneal thickening, with no associated gastrointestinal symptoms, ascites or omental nodules (3). Massive ascites is not commonly associated; however, a small to

moderate amount of fluid collections in peritoneal and pleural spaces are frequently seen, because of the transdiaphragmatic spread. The initial diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma is time consuming

and arduous in the absence of evident symptoms. Examination of the ascitic fluid could lead to dubious interpretation, becoming positive only in the late phases (8). Radiological methods can

contribute to the formulation of a diagnosis, but obtaining a biopsy specimen during laparoscopy or laparotomy is still procedure of choice. Findings of an image-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy

should be interpreted with caution because the results may be misleading. That is why some authors favor the use of a laparoscopic biopsy as it permits direct visualization and abdominal staging (3).

The differential diagnosis includes peritoneal carcinomatosis, lymphomas and tuberculous peritonitis. Treatment, including systemic and intraperitoneal chemotherapy, abdominal radiotherapy and

surgical debulking have all been used with little success, resulting in short median survival (4–12 months) (3). The nonspecific nature of the symptoms often leads to a delay in making a

diagnosis, which contributes to the high mortality rate, irrespective of the modality of treatment. However, it is hoped that with earlier diagnosis and radical treatment, the survival rate of

patients may be improved (3).